By Zoie Matthew

LAist – Published Nov 16, 2021 8:10 AM

Since opening its doors more than a decade ago, Proof Bakery in Atwater Village has become a pastry powerhouse. Every weekend, a line of hungry customers stretches out the door and onto Glendale Boulevard, waiting to get their hands on cardamom morning buns, kabocha tea cakes, fresh-baked baguettes and flaky croissants. If regulars had been paying attention in August 2021, they would have noticed a new, hand-painted sign on the front door, reading, “A WORKER-OWNED COOPERATIVE.”

In August 2021, Proof founder Na Young Ma, a Los Angeles native who trained at the Culinary Institute of America, sold her bakery to her employees. It’s one of a small but growing number of L.A. food businesses forgoing traditional corporate structures in favor of worker-owned co-ops.

Alongside Ma’s bakery, start-ups such as Public Access Co-Op, Nice Big Table and Pueblo Cafe have embraced this centuries-old (but still rare) business model, in which employees own and jointly manage the business they work for while profiting directly from their labor.

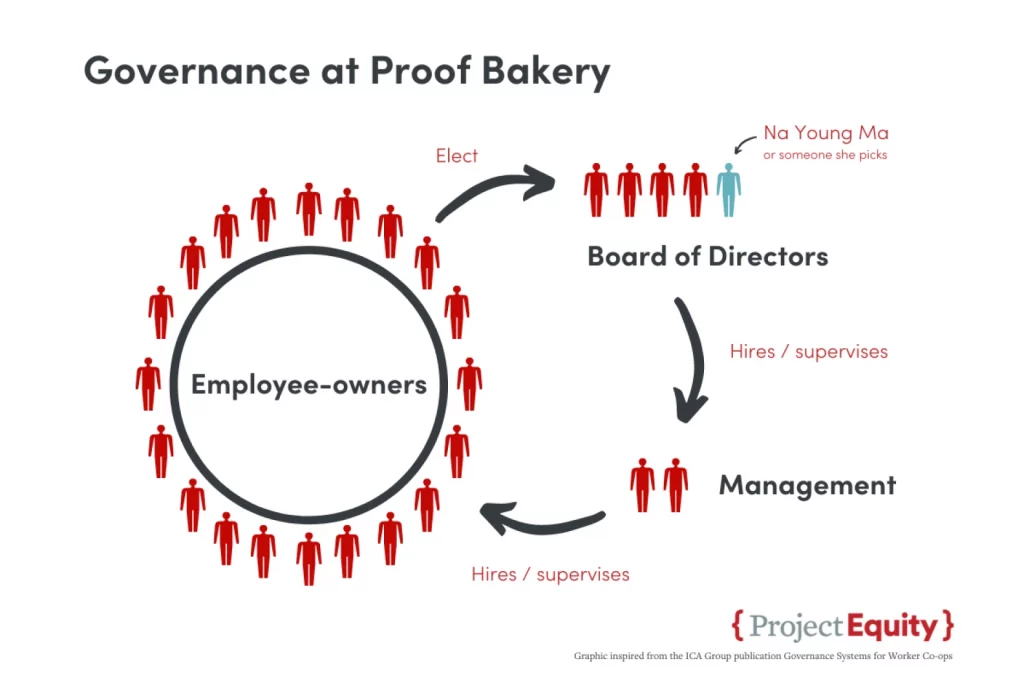

(Courtesy of Franzi Charen/Project Equity)

First popularized during the industrial revolution, when striking workers formed co-ops to support themselves, the model has seen widespread success in some parts of Europe, such as the Basque region of Spain. In the United States, its popularity tends to peak during times of financial hardship or turbulence. Cooperative bargaining systems served more than a million people during the Great Depression. The number of worker co-ops spiked again in the decade following the Great Recession.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has laid bare the physical, psychological and financial toll of restaurant work, some employees and owners are once again turning to co-ops in the hopes of making the food industry less exploitative and more sustainable. Whether they’re starting from the ground up or transitioning from more traditional business models, these scrappy worker-owned establishments have a long road of financial and practical challenges ahead of them.

(Courtesy of Franzi Charen/Project Equity)

One For All, All For One

With the motto “not business as usual,” L.A. Co-Op Lab is a non-profit that consults with businesses hoping to implement a worker-owned model. (Yes, it’s also run as a worker-owned co-op.) During the pandemic, co-founder Gilda Haas says the number of informational requests about worker-owned business models has tripled. At least half of them came from the food industry.

“People started reconsidering, existentially, what their work lives should be like. People who work in food — chefs, for example — just didn’t want to go back to that crazy, hierarchical kitchen culture,” Haas says.

That’s what happened to Johnny Murphy, a former pastry chef at Echo Park’s Konbi. Murphy says that even before the pandemic, he and his coworkers spent many late nights talking about the inequities of the industry, the lack of stability and the high-pressure kitchen environment. Once COVID hit, he and many of his colleagues were laid off, so he reached out to fellow Konbi workers and food industry friends with the idea of starting a co-op.

“We started thinking about what we could do to make a more equitable situation for workers in general but also to address issues like food deserts and the fact that there’s places in inside L.A., one of the biggest cities in the world, where you cannot get fresh vegetables,” Murphy says.

(Courtesy of Franzi Charen/Project Equity)

Working with L.A. Co-Op Lab, Murphy and eight other worker-owners formed Public Access Co-Op in the spring of 2021. Since then, they’ve released five meal boxes via Instagram, all partnered with local chefs and restaurants including Estrano, Pine and Crane, pastry chef Shannon Swindle, Perilla and, most recently, Murphy’s former employer Konbi. Customers pick up their boxes from the youth homelessness organization Covenant House, which the co-op has partnered with and donates 25% of proceeds to. They also cook meals for residents on pickup days.

Partially inspired by the Mandela Grocery cooperative, a worker-owned grocery store in West Oakland that has been operating for more than a decade, Public Access Co-Op hopes to eventually open a brick-and-mortar market, maybe several markets, in L.A. neighborhoods with high levels of food insecurity.

“In addition to providing communities with food and access to local produce, I think it’s important to build up a community of kitchen people who have had pretty fucked up work experiences for a long time,” says worker-owner Greg Davis. “Making a place for them where they feel like their labor is appreciated and they actually have some say in things will be very uplifting for a ton of people, regardless of their position.”

For Pueblo Cafe, a pop-up coffee co-op based in South L.A., the worker-owned model is also a way to build community. Inspired by the principles of the Zapatista coffee cooperatives in Mexico from whence they source some of their coffee, they hope to open a cafe where they can host cultural and political events. They want to serve as a hub for South L.A. residents fighting the gentrification in their neighborhood.

“The cooperative model was ideal for us because we wanted to create a community space and really be values-driven,” says Pueblo Cafe worker-owner Ellie Guzman. “So when we talk about sharing resources, sharing knowledge and sharing power, that’s what we’re also modeling ourselves, within our own business model.”

Before Pueblo Cafe can do that, they’ll have to face the same challenges as any start-up business — building a customer base, smoothing out any number of logistical and technical issues, finding a suitable location and pulling together enough money to secure it, something they’re trying to do through catering, pop-ups and fundraising events. “The Zapatistas talk about ‘un mundo de muchos mundos,’ or having a “world of many worlds,'” Guzman says. “I’m really excited and passionate about creating this from the ground up to offer an alternative to what currently feels like the norm, and what we feel like is the only choice we have when it comes to jobs and the way businesses are run.”

(Courtesy of Franzi Charen/Project Equity)

There’s More Than One Way

Starting a worker-owned cooperative from the ground-up is rare and comes with a host of unique challenges. Transitioning an established business from corporation to co-op might be even more difficult. For starters, the owner needs to be willing to sell their business. In the rare cases when someone is happy to do that, transitioning can be a long, expensive and complicated process.

Alison Lingane, co-founder of a nonprofit called Project Equity, which helps existing companies transition to employee ownership, says the worker cooperative model works better for some businesses than others. For instance, full-service restaurants with complex staffing structures and lower profit margins often have a challenging time converting.

“The food service businesses that are going to be more successful transitioning to employee-owned are the ones that have more focused product lines… a bakery or a pizza place that’s not offering a full sit-down breakfast, lunch and dinner menu,” Lingane says.

(Courtesy of Project Equity)

Some L.A. business owners have experimented with hybrid approaches to incorporating workers into business decisions. For years, Sol Salzer of City Bean Roasters has been trying to convert his Mid-City coffee company to an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (or ESOP). This employee ownership model, which is more common in the U.S. than the worker cooperative, allows staff members to become shareholders in a company. However, pandemic budget cuts made it difficult to pay for legal fees or expand the company enough to complete the transition.

In the meantime, Salzer has introduced a profit-sharing program as well as a democratic hiring process that allows employees to have a say in who comes on board. “What we’ve done is we’ve changed the culture within the company, so when we’re ready to make that transition from corporation to ESOP, the culture is already in place,” Salzer says.

The new owners of Fairfax’s Diamond Bakery implemented a similar profit-sharing model earlier this year, following a period where the original owners stepped away and the workers were briefly in charge.

For businesses that have the desire and ability to fully transition, worker-ownership models can offer long-term benefits to sellers, according to Lingane. There are often tax perks involved. Also, owners who are looking to retire but don’t have anyone to leave their business to can be assured it stays in trustworthy hands.

“The legacy piece, for many, is the primary driver of wanting to do this, wanting your business to live on in a really positive way that’s benefiting others. We’ve talked to many business owners who say, ‘Gosh, half of my employees have been with me for 10 or 15 years or more, and I’m so excited to be able to see them step into ownership as I’m stepping out,'” Lingane says.

Ma had long been inspired by the successful Bay Area co-ops such as the Arizmendi Bakery chain and The Cheese Board. When she decided in 2019 it was time to step back from running Proof, she found it hard to imagine another path for her business.

“You hear stories of people selling a business to someone and then they lay off the employees, change the products and even change the name and rebrand. That possibility was sad for me, with the years of hard work and sweat it took to build this up,” Ma says.

(Courtesy of Franzi Charen/Project Equity)

She reached out to Project Equity, which worked with the team at Proof to make the transition to co-op. It was no small task. Once Ma found enough workers who were interested in being part of the transition team (four people plus herself, to be precise), they had to go through a three-month process of assessing the bakery’s financial stability.

Since every co-op operates differently, they also had to set up Proof’s internal system of governance and craft the bylaws that would determine how it would operate. For instance, they decided that employees must work at the bakery for at least a year before they can become a worker-owner. Employees also had to be given a chance, literally and conceptually, to buy into the new business plan. Becoming a worker-owner would require them to invest between $2,000 and $2,500, either up-front or deducted from future paychecks. In the end, approximately 11 of Proof’s 24 employees decided to step into ownership roles. These worker-owners now have the ability to vote on decisions about things like benefit packages, pay and major changes to the business. The remaining workers function as traditional employees.

(Courtesy of Franzi Charen/Project Equity)

Proof worker-owner Sarah Brown says that while day-to-day operations at the bakery have stayed the same, the way employees think about their workplace has changed significantly. Shifting from a hierarchical kitchen culture to one where they have a stake in the decision making process is a huge mental adjustment.

“We were so ingrained, especially those of us who have been in food for a while, into this traditional model of taking orders,” Brown says.

Part of her job now is helping to determine what constitutes a minor “operational” decision that can be decided by the management team without a vote (such as a pricing change) and what requires the input of all co-op members. For instance, a recent decision about a two-day holiday pay increase turned into a larger discussion about the value of workers’ time during one of the bakery’s busiest seasons.

“What if we were to be intentional about giving holiday pay that lasted for the entire season, or finding some other creative solution? That’s an example of something that would be traditionally operational, but we are now having more of a cultural conversation that co-op members can vote on,” Brown says.

After several months, they’re still working out the kinks. “It’s kind of messy. We’re learning it’s not all black and white,” Ma says.

Lingane says these growing pains are normal. It’s part of the reason Project Equity works with businesses for at least two years post-transition.

“There definitely are shifts. How are decisions made differently now? Who do you look to for things? Where do you give input when there wasn’t a formal input process for things before, and there is now?” Lingane says.

(Courtesy of Franzi Charen/Project Equity)

While the transition to worker-owned co-op hasn’t always been smooth sailing at Proof, Brown thinks it has, ultimately, been worth it. Workers are now more empowered to make decisions about issues that impact their lives.

“Within the food industry, it’s really very rare to come across an environment where the people at the top, or really anybody within the structure, is willing to ask for opinions from everybody,” Brown says.

Ma says after the year-and-a-half of work it took to establish Proof as a co-op, her dominant feeling is relief.

“When I was owning this business and it was just all me, there was this burden. However much I loved doing this, it was just the stress of, okay, I’m the only one who will have to come in at night if the fridge dies,” Ma says. Now, she has partners to help her handle emergencies and make tough decisions.

Moving forward, Ma hopes Proof will serve as an example for other local food businesses that are looking to change the industry. Perhaps it will spawn a network of worker-owned businesses that collaborate with and support each other.

“One of the co-op principles is ‘cooperation among cooperatives.’ If your co-op works with another co-op, it grows,” Ma says. “That would be a future goal for Proof because we are here as an example. This can grow.”